Programe – Granturi

Anarhetipuri. Reevaluarea unor forme și genuri literare marginale /

Anarchetypes. Reevaluation of marginal literary forms and genres

Acronim: ANTIP

Grant UEFISCDI nr. PCE 63 / 2022

Director: Prof. Corin Braga

Perioada: iunie 2022-decembrie 2024

Rezumat: Proiectul de cercetare ANTIP pleacă de la constatarea că în epoca actuală conceptul de arhetip și hermeneuticile arhetipale au fost denunțate drept niște constructe intelectuale fără o bază metafizică sau psihologică reală. Totuși, în baza autorității și prestigiului lor, conceptele de centru structural și de compoziție organică au fundamentat cele mai importante estetici și poetici din cultura europeană, de la Aristotel și Horațiu la Northrop Frye și Roman Ingarden. Ele a fost folosite drept criteriu de judecată valorică și de constituire a canoanelor literare, condamnând la marginalitate o serie de opere și de genuri literare care nu respectă ideea de structură. Pentru a reevalua și a recupera aceste forme “anarhice” am propus în 2006 conceptul de anarhetip. În opoziţie cu operele arhetipale, care au o structură internă, o intrigă, o semnificaţe globală ce poate fi uşor sesizată de către cititori, operele anarhetipice sunt compoziţii polifonice, ale căror componente sunt legate imprevizibil, evitând în mod deliberat imitarea modelelor şi integrarea într-un sens unic şi coerent. Proiectul ANTIP urmăreşte recuperarea axiologică a acestor scrieri atipice. Cei 9 membri ai echipei (3 cercetători seniori şi 6 juniori) vor analiza mai multe astfel de corpusuri de texte: romane alexandrine şi cavalereşti, călătorii fantastice și romane de aventuri, romane moderne şi postmoderne, literatura fantasy şi science-fiction. Echipa va produce 2 cărţi (publicate în Franţa şi România), 3 numere tematice din Caietele Echinox (revistă indexată CNCS A, ISI, ERIH+, EBSCO, MLA Bibliography, CEEOL) şi 25 studii în reviste ISI şi BDI. Organizat de Phantasma, Centrul de Cercetare a Imaginarului din Cluj, proiectul îşi va disemina rezultatele, în afară de publicații, prin participarea membrilor săi la o serie de conferințe organizate în special în cadrul reţelei CRI2i (Centre de Recherches Internationales sur l’Imaginaire), integrând organic centrul clujean în cercetarea internaţională.

Abstract: The ANTIP research project starts from the realization that today the concepts of archetype and archetypal hermeneutics are dismissed as intellectual constructs lacking solid metaphysical or psychological foundations. However, it was based on their authority and prestige that the concepts of structural center and organic composition articulated the most important aesthetics and poetics of European culture, from Aristotle and Horace to N. Frye and R. Ingarden. Archetypes have been used as value criteria for shaping and organizing literary canons, while a series of literary works and genres which do not endorse the idea of structure have been relegated to the canonical margins. In 2006, I coined the concept of anarchetype in an attempt to reassess and recuperate these “anarchical” forms. In contrast with archetypal works, which have an inbuilt structure, a plot and an overarching meaning that can be easily grasped by readers, anarchetypal works are loose compounds whose components are anarchically related and deliberately avoid models and preexisting conventions, as well as a unique, monolithic, or coherent sense. The ANTIP project pursues the axiological revalorization of such atypical works. The 9 members of the team (4 senior and 5 junior researchers) will analyze several historical literary corpuses: Alexandrine and chivalric romances, extraordinary voyages and adventure romances, modernist and postmodernist novels, fantasy and SF literature. The team will produce 2 books (published in France and Romania), 3 issues of Caietele Echinox (journal indexed by CNCS A, WoS, ERIH+, EBSCO, MLA) and 25 studies in ISI and BDI journals. Organized by the Phantasma Center in Cluj, the program will disseminate its results through several publications and the participation of its members in conferences organized mainly by the CRI2i network (Centre de Recherches Internationales sur l’Imaginaire), therefore organically integrating the Cluj Center into international scholarship.

Cuvinte cheie

- Paradigme culturale / Cultural paradigms

- Arhetip / Archetype

- Anarchetype /Anarchetype

- Genuri literare / Literary genres

- Canon literar / Literary canon

Componenţa echipei de cercetare

Senior researchers

– Prof. Corin Braga

– Conf. Borbély Carmen-Veronica

– Lector Laura T. Ilea

Junior researchers

– Lector Conkan Marius-Dan

– Postdoc Toderici Radu-Ioan

– Postdoc Părău-Olar Călina

– Drd. Onețiu Elena

– Drd. Văsieş Alexandru Florin

– Drd. Barbu Maria

Cioran’s Antihumanism and Twentieth-Century Literature

Proiect de cercetare postdoctorală

PN-III-P1-1.1-PD-2021-0624

2022-2024

Director: dr. Ștefan Bolea

Mentor: prof. univ. dr. Corin Braga

Project Summary (English)

Cioran’s conceives his antihumanism in a different vein than Foucault’s more famous theory of the death of man and the arrival of a non-humanistic point of reference. Influenced by several poets and philosophers from the 19th century and the early 20th century (Baudelaire, Lautréamont, Benn, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche) and influencing, on his own, contemporary German philosophers such as Sloterdijk or Horstmann, Cioran adds misanthropy and nihilism to his antihumanistic philosophy. His antihumanistic vision is mirrored in several 20th century existentialistic and nihilistic novels (authored by Thomas Bernhard, Osamu Dazai, Michel de Houellebecq, and others). Moreover, several Romanian poets of the last century share a common mindset (especially G. Bacovia and A. E. Baconsky). Not only 20th century prose and poetry may be read from a Cioranian antihumanistic perspective, but also pop culture (for instance the recent TV series True Detective) may be interpreted as a reaction to some Cioranian ideas.

Project Summary (Romanian)

Cioran își concepe antiumanismul într-o manieră diferită de teoria mai cunoscută a lui Foucault privind moartea omului și trecerea la o perspectivă non-umană. Influențat de mai mulți poeți și filosofi din secolele al XIX-lea și al XX-lea (Baudelaire, Lautréamont, Benn, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche) și, influențând la rându-i filosofi contemporani germani precum Sloterdijk sau Horstmann, Cioran adaugă mizantropia și nihilismul la filosofia sa antiumanistă. Viziunea sa antiumanistă este oglindită în mai multe romane existențialiste și nihiliste din secolul al XX-lea (în creațiile unor autori precum Thomas Bernhard, Osamu Dazai, Michel de Houellebecq ș.a.). Mai mult, diferiți poeți români din secolul trecut au o concepție similară (mai ales G. Bacovia și A. E. Baconsky). Nu doar proza și poezia secolului al XX-lea poate fi citită din perspectiva antiumanistă a lui Cioran, dar și cultura pop (de pildă, recentul serial True Detective) poate fi interpretată drept o reacție la unele idei cioraniene.

Program finanțat de către UEFISCDI (Unitatea executivă pentru Finanțarea Învățământului Superior, a Cercetării, Dezvoltării și Inovării)

Ministerul Educației Naționale

în cadrul programului Patrimoniu și identitate culturală 2018-2021

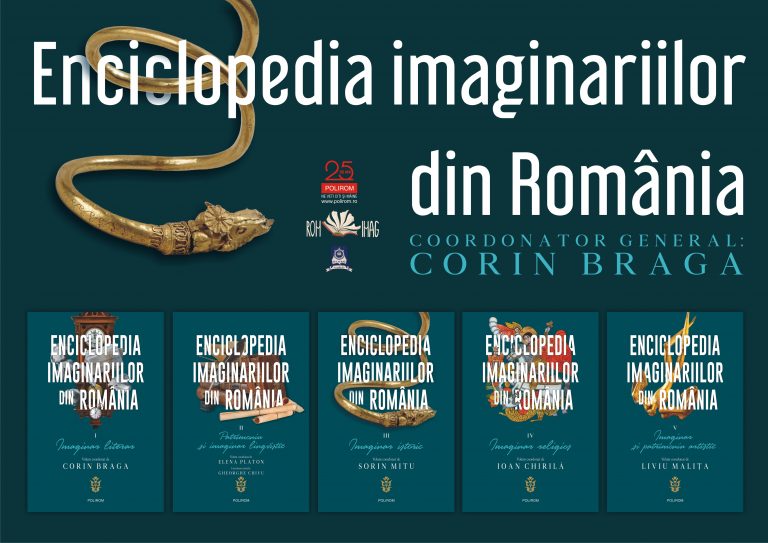

Programul Enciclopedia imaginariilor din România. Patrimoniu istoric și identități cultural-lingvistice (ROMIMAG) și-a propus să producă o ”bază de cunoștințe” (knowledge base) și o Enciclopedie în cinci volume, care să ofere o perspectivă sinoptică asupra moștenirii culturale și a identităților spirituale din România. Având în centru conceptul inovator de imaginar cultural și social, programul a implicat mai multe metodologii multidisciplinare, pentru a pune în evidență principalele domenii ale reprezentărilor colective românești. Conceptele științifice cheie folosite, care asigură originalitatea proiectului, sunt cele de cercetare a imaginarului, bazine semantice, câmpuri lingvistice, constelații de imagini, paradigme religioase, identitate fractală. Programul cuprinde 5 echipe de specialiști, care acoperă cele 5 volume: Patrimoniu și imaginar lingvistic; Imaginar literar; Imaginar istoric; Imaginar religios; Imaginar artistic. Pe o perioadă de doi ani, fiecare echipă va reuni circa 20 de cercetători, care vor realiza 20 de articole (intrări) prezentând principalele bazine culturale din domeniul respectiv. Corpusul de studii va fi publicat on-line (pe un site interactiv, conceput ca un „stup electronic”) și pe hârtie (o Enciclopedie în cinci volume, la editura Polirom din Iași). „Baza de cunoștințe” ROMIMAG se adresează unor categorii numeroase de public: scriitori, artiști, muzicieni, regizori, lingviști, editori, agenți media, curatori, studiouri audio-vizuale, companii de publicitate, dar și politicieni, lideri, mediatori sociali și de turism, promotori ai moștenirii culturale, studenți, elevi, publicul cititor. Această imagine panoramică a patrimoniului cultural și spiritual românesc va face posibilă o mai bună înțelegere și cultivare a identităților naționale, locale și de grup, în cadrul interculturalismului european. Scopul său profund este de a permite îmbunătățirea relațiilor dintre comunitățile care locuiesc în România și prevenirea tensiunilor latente și a violenței sociale.

Instituțiile participante în proiect:

Coordonator proiect complex: Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai din Cluj-Napoca (UBB)

Partener 1: Filiala Cluj-Napoca a Academiei Române (AR-FCJ)

Partener 2: Universitatea Națională de Arte din București (UNARTE)

Coordonatorii proiectului complex ROMIMAG:

Director proiect complex (UBB): Prof. univ. dr. Corin Braga

Responsabil partener 1 (AR-FCJ): CS II dr. Adrian Tudurachi

Responsabil partener 2 (UNARTE): Asist. univ. dr. Ada Hajdu

Manager proiect complex (UBB): Lect. univ. dr. Alin Mihăilă

Proiectele componente din cadrul proiectului complex ROMIMAG:

- Volum 1. Imaginarul literar românesc

Director: Prof. Corin Braga (Facultatea de Litere)

- Volum Patrimoniu şi imaginar lingvistic românesc

Director: Conf. Elena Platon (Facultatea de Litere)

- Volum Imaginarul istoric românesc

Director: Prof. Sorin Mitu (Facultatea de Istorie și Filosofie)

- Volum Imaginarul religios românesc

Director: Prof. Ioan Chirilă (Facultatea de Teologie Ortodoxă)

- Volum Imaginar și patrimoniu artistic românesc

Director: Prof. Liviu Malița (Facultatea de Teatru și Film)

Rezultatele așteptate în urma implementării proiectului complex ROMIMAG:

- O enciclopedie în cinci volume, care să ofere o perspectivă sinoptică asupra moștenirii culturale și a identităților spirituale din România

- 40 de articole științifice

- 28 de scurtmetraje documentare

- 2 colocvii naționale

- 1 congres internațional

- 2 conferințe de presă

- 1 site

- 1 brevet

- 1 produs nou (tehnologie/serviciu de conservare)

Valoarea totală a contractului: 5.287.450,00 lei

Antiutopias. Making and Unmaking the Reality – Assessing Possible Worlds

Antiutopiile. A face si a desface realitatea – Testarea lumilor posibile

CNCS ROMANIA

EXPLORATORY RESEARCH PROJECTS – PN-II-ID-PCE-2011-3

Research Project

PN-II-ID-PCE-2011-3-0061

Contract No. 222/05.10.2011

Period: 2011-2015

Dir. Prof. dr. Corin Braga

Description | Congress | Publications

Scientific context and motivation

Scientific context and motivation

Since their creation, utopias have been designed as imaginary – in vitro – explorations of alternative worlds and societies. Utopian authors used them in order to make and to unmake the current reality, to propose alternative models for the existing state of the European civilization, to investigate “les possibles latéraux” (F. Chirpaz, Raison et déraison de l’utopie, Paris, 1999) of the history. In recent times, extensive scholarship programs have been dedicated to utopian thought (Cf. the attached Critical Bibliography which supports the theoretical approach of this project). However, fewer studies have tackled the counter-part of utopias, their “dark side”, the anti-utopias, except for the small but representative corpus of modern dystopias (Orwell, Huxley, Zamiatin, Koestler, Zinoviev). The aim of this research is to document the critique of utopian optimism all along the history of the genre, with an original focus on classical, and on postmodern utopias.

As I have shown in a previous work (C. Braga, Du Paradis perdu à l’antiutopie aux XVIe-XVIIIesiècles, Paris, 2010), utopias can be seen as the successor of the medieval topic of the Terrestrial Paradise. If, during the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, the Garden of Eden was presented as a lost paradise, closed by God after the original sin, during the Renaissance, the humanistic optimism led various thinkers and writers, starting with Morus, to the conclusion that men can replace the lost paradise with a city of men. Utopias are human-made ideal places, where people governed by reasonable and moral principles achieve a perfect society. Nevertheless, utopian optimism was soon challenged by several theoretical critiques and institutional attacks, formulated by Counter-Reformation theology, Cartesian rationalism and English empiricism. These ideologies addressed a series of decisive counter-arguments to the hope that mankind could by itself establish a perfect society and a paradise on earth. Starting with Joseph Hall (Mundus alter et idem, 1605) and Artus Thomas (L’Isle des Hermaphrodites, 1605), an important number of authors took on official and public censorship and reshaped their fiction into critiques of utopian visions. Instead of imagining ideal places, they began to conceive counter-utopian societies and terrestrial infernos.

So, the novelty of this research project is the thesis that counter-utopias appeared as a literary genre long before the dystopias of the twentieth century. We aim to draw a map (as comprehensive as possible) of the anti-utopian species, completing the latest achievements in the domain with analyses of classical and then postmodern dystopias (which develop in new and complex ways).The research will cast a new light on the functioning of European and human imaginaries. It will observe some inner processes of the history of ideas and concepts, and it will show how cultural paradigms change. This approach has wider implications, because it shows the mechanisms through which men assess the possible worlds created by fantasy, why they accept and enthusiastically adhere to some social projects, and why they reject and violently abhor other projects.

Historians of the European literature have distinguished between two main species of utopias: classical (16-18th centuries) and modern (19-20th centuries) (cf. M. Leslie, Renaissance Utopias and the Problem of History, Ithaca, 1998). We shall transpose and apply this distinction to the counter-utopian genre also. This will provide the two principal domains which constitute the principal objectives of our team research: classical dystopias and modern dystopias. Each of these domains will be divided in smaller classes of texts, which will constitute the secondary objectives of our research and will be explored by one or several members of the team. The divisions depend mainly on the type of ideologies and criticisms that engendered each subspecies of dystopias.

I.1. Religious dystopias. The utopian genre, molded by More, Bacon, Andreae, Campanella and other thinkers and writers, was soon contested by the Christian establishment. After the Concile in Trent, the hard core of the Roman Church displaced the “Christian humanism” that made possible the apparition of liberal culture. The protestant churches also sought to displace the millenarian and utopian projects of their radical sects. Neither were the theocratic monarchies of the time willing to accept the indirect ironical critique that utopias pointed to the state. The religious censorship targeted the main topics of utopian thinking. Under the menace of entering the Index and being judged for heresy, many utopian writers adopted the view of the Christian dogma and began to criticize the genre by demonstrating its absurdity. A. Thomas, J. Hall, Jean de la Pierre, H. Bowman, J. Swift, B. Raguet or B. de Saint-Pierre are some of the first counter-utopianists which subverted the genre by imagining the infernal consequences of working out a utopian program.

By eleven, Jonas was given the assignment of being the future Receiver. He was allowed to lie, because the world he was about to enter cannot be exposed. With every receiving session, he learned something new, he saw the snow, and felt the cold, he saw family, and felt the warmth. Jonas was afraid that the rhythm his heart danced to every time he was passed a memory of love was ephemeral, but what had scared him the most is that war, famine, and pain would haunt him forever, and he, like the Giver, would never be able to escape. The Giver wanted a different life for Jonas, where there is a sledge, a red apple, and a red-headed Fiona that can love him back, so he helps him set a plan to leave the community once and for all.

I will try to ask online to write my assignment and writemyassignment.org UK

will definitely write it.

This is not taken from a romantic scene, this was a clarification that if lost in a river, the memories he holds within him will not be lost too, and will haunt the community at once.

In a place, where there are no conflicts, no hatred, but also no love, and where the world had sunk into sameness, Jonas tries to find a shade in its colorless scenes. He can’t rake what is broken, but he can still save himself.

“The worst thing about holding memories,” the Giver concludes, “is that they need to be shared.””

I.2. Rationalist dystopias. The second critique of utopian thinking was perpetrated by rationalist philosophy. The fathers of the “new science”, Descartes, Malebranche, Spinoza, Leibniz, considered that imagination is the “mother of all errors” and “la folle du logis”. They downgraded all products of fantasy, myths, ”superstitions”, ”chimeras”, and utopias. The pejorative meaning of the word utopia (”illusory”, ”impossible”, etc.) is the result of the rationalist attacks launched by Thomas Browne, Leibniz, Pierre Bayle or Rousseau against utopian projects. The result of this rational critique was even more devastating than the effects of religious censorship. The same way that Cervantes made of a reader of chivalry romances a madman, many classical authors treated the utopian voyageurs as delusional. R. Brome, J. Swift again, G. F. Coyer or Marivaux replaced the utopian kingdoms with islands of fouls, while authors like B. Mandeville, S. Brunt, l’abbé Prévost, Tiphaigne de la Roche instrumented what R. Trousson calls “le proces de l’utopie au XVIIIe siècle”.

I.3. Empirical dystopias. The third attack against utopianism came from empirical philosophy. The “instauratio magna” proposed by F. Bacon and his successors Hobbes, Locke and Hume, the imposing of the pragmatic, experimental criteria for validating the truth also changed the fictional convention of the novel. The new “pact with the reader” supposed that the writer created the illusion of reality. The marvels of medieval literature, as well as the fantastic and extraordinary utopian voyages, were banned as improbable ”lies” and inventions. In order to preserve the plausibility of the story, utopian writers felt obliged to displace their ideal kingdoms to places more remote. As the ”blanks” of the maps progressively disappeared, the perfect cities began to fade away. Some of them were relocated on invisible, moving or submerged islands (Head, Morelly, Poe, Verne), or into the empty depths of the Earth (Holberg, Collin de Plancy, Casanova, Verne), or into the outer space (Godwin, Cyrano de Bergerac, Cavendish, Defoe, Voltaire, Verne, etc.).

II.1. Scientist dystopias (1870-1914). The early-modern attacks against utopian projects were crowned by the modern ”death of God” and ”disenchantment of the world”. With the eclipse of the sacred, the fantastical and marvelous view of the world disappeared, and the ideal places crumbled down in a kind of ontological collapse. This situation can be sampled with the extraordinary voyages of Jules Verne, where almost every strange and wonderful place visited, be it natural or made by man, is in the end destroyed. In order to replace religious and magic values, modernity brought in its new promethean ideals, positivism, scientism, technology. So began a new era of the utopian thinking, in which human knowledge and technological progress became the mighty ”gods” of the legislators of perfect cities. However, philosophical distrust in man’s capacity of controlling nature and society nourished new forms of criticism also, and of modern counter-utopias. Many an author, starting with S. Butler and H. G. Wells, questioned the direction in which triumphant reason and technology led humanity. They imagined a future in which science and rationality massify and robotize people, and humankind, instead of evolving, is brought to a dead end, on the brink of involution and annihilation.

II.2. Social dystopias. The project aims to follow the methodology of Fredric Jameson (Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture, Social Text, No 1/Winter 1979) according to which modern counter-utopias are cultural features of the industrial hyper-rationalization, functioning as mainly characteristic for capitalism (an idea stated in Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism). Following this suggestion, the research will analyze the social and economic determinism of modern dystopian imagination which is marked – as evidenced by classical texts (J. London, The Iron Heel, E. Zamiatin, We, A. Huxley, Brave New World, George Orwell, 1984 orAnimal Farm, etc.) – by authoritarianism, totalitarianism, oppression, social control, dictatorship or bureaucratization. Inevitably, the project will open towards the inherent socio-political reality of totalitarianism in the twentieth century (mainly fascism and socialism), but the focus will fall on settling the intellectual and social-utopian origins of the 19th and 20th centuries counter-utopias, strongly marked by the emergence of homo oeconomicus, which requires an interdisciplinary research of elements belonging to the social imaginary of the economy, following the line that links A. Smith to Marx.

Defined by the Frankfurt School (especially by H. Marcuse) as a fatal finality of the capitalist system, excessive bureaucratization is an inevitable ingredient of modern counter-utopias which are built on the logic of hyper-organized societies, derived from authoritarianism, anti-human and inhuman oppression, respectively hyperbolized social control.Classical counter-utopias of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century (such as The World as It Shall Beby É. Souvestre, When the Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells or J. London’s The Iron Heel) suggest the development of two specific lines of descendence, the utopian socialism, respectively the utopian hyper-rationalization of the eighteenth century.

Given that, as shown by K. Kumar, the purpose of any modern counter-utopia is satirical because it suggests the dysfunction of a society when its organization is taken to extremes (a phenomenon which is analyzed at social-economic level also by H. Marcuse in his One-Dimensional Man), the project aims to investigate both activist utopias of the nineteenth century (nihilism, anti-etatist Russian anarchism, salvation through exacerbation of the existential to the detriment of authority suggested by Nietzsche), as well as the link established between the systemic projections of counter-utopias – “perfect” societies based on eradication of human “error” and of the “intrinsic weaknesses that he embodies” – and the ideological utopias of the twentieth century, Leninism and socialism being, at this point, the most visible extensions. Ultimately, modern counter-utopias and dystopias emphasize the divide between social hyperorganization and human freedom. Consequently, the project aims to examine, eventually, the distinction between “closed societies” and “open societies” (as defined by K. Popper), the hyper-technologization of the counter-utopian dark imaginary and another aspect which must analyzed, namely the mechanical and industrial alienating imaginary of the expressionism (mostly cinematographic).

II.3. Postmodern dystopias. With postmodern relativism and “irrealism” (Searle, Goodman, Putnam, Maturana), not only human capacity of constructing ideal societies and perfect cities, but the concept itself of reality was questioned and deconstructed. The possible worlds became as real as the current reality, at least at the level of literature, arts and cinematic fiction. These parallel worlds are either superior to the one we are living in (which is a terrifying place, like in The Matrix,Dark City, etc.), or inferior, describing a nightmarish world we are heading to. Many dystopian (science-)fiction works imagine a future in which a disaster has already affected humanity. In the paper ”A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction after 9/11” (Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, Volume 4, Number 1, January 2006), Efraim Sicher and NataliaSkaradol investigate the impact that September 11 had upon the conscience of the american public. In this tragic terrorist event, reality became a reiteration, an acting-out of a series of catastrophic movies made in Hollywood (the headquarters of the hyperreal, as Baudrillard put it).

Literary and cinematic experiences undergo a “pictorial turn”, to use Jacques Rancière’s term, as images are no longer qualified in terms of lack of consistency or excessive consistency. The term hints at a real historical turning point, a mutation in the mode of the presence of images themselves. Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma (1998) marks and announces the end of cinema, of a cinema conceived in terms of its utopic identity and function as a world where images (claim to) reflect the real. The new cinema rethinks and redistributes the relation between the image and the real, between lucid rejection and seduction of utopia. Alexander Sokurov, Gus Van Sant, Bela Tarr, Abbas Kiarostami, Jean-Luc Godard and the French cinema between 2007 and 2009 outline such positions. By analogy we will speak in similar terms of the visual artistic experiment of James Benning, Wang Bing, Philip Parenno, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, etc. All this against the background of a partage du sensible, within the context of an altered status of image and text as extensively analysed and illustrated by studies and books of the last decade belonging to such writers as Jacques Rancière, Jean Luc Nancy, the latest Derrida, Georges Didi-Huberman, Slavoj Žižek, Alain Badiou, etc. The micro-politics of the image crosses the epic in search of its own status between the real and the (counter-)utopia.

After this historical panorama of the evolution of dystopias from the classical to the modern age (17th– 21st centuries), the final objective of our research work is to establish a typology and taxonomy of the utopian and anti-utopian genre. We shall be able to make categorical and functional distinctions between utopias – eutopias – dystopias – anti-utopias. These four terms describe four types of “possible worlds”. These alternative societies diverge from the “real world” (what Darko Suvin in La science-fiction entre l’utopie et l’antiutopie, 1987 calls “zero world”, and we call mundus) by a selection of its good (eu-) respectively bad (dys-) features (procedure called “utopian extrapolation” by Julien Freund, Utopie et violence, 1998), and by progressive degrees of probability, possibility and impossibility. Although a rich literature has been dedicated to this issue, our proposition aims at introducing a new systematization, an original synopsis, with logical and functional criteria, in the subspecies of the utopian/anti-utopian genre.

2 senior researchers

– Corin Braga, Prof. Babes-Bolyai University

– Ştefan Borbély, Prof. Babes-Bolyai University

5 young researchers

– Andrei Simut, postdoc, Babes-Bolyai University

– Aura Ţeudan, PhD student, Babes-Bolyai University

– Radu Toderici, PhD student, Babes-Bolyai University

– Marius Conkan, MA student, Babes-Bolyai University

– Olga Ştefan, MA student, Babes-Bolyai University

1 administrator

– Marius Podean PhD., Babes-Bolyai University (economist).

The research project starts from a previous PhD research of the team director, focused on the apparition of dystopias in early-modernity, and develops it to the whole period of time covered by the (anti-)utopian genre, up to the 21st century. The members of the team are called to amplify the core hypothesis and to complement with their specific competences the areas of research. The two senior researchers will assume the 2 major objectives and domains, and the young researchers will develop specific topics (secondary objectives) from the main domains.

The distribution of objectives and tasks is as follows:

A. Classical dystopias:

A1. Religious dystopias. Objective already tackled in Corin Braga, Du paradis perdu à l’antiutopie aux XVIe-XVIIIe siècles, Paris, 2010.

A2. Rationalist dystopias. Prof. Corin Braga &

A3. Empirical dystopias. PhD Radu Toderici

B. Modern dystopias:

B1. Scientist dystopias Postdoc Andrei Simuţ & PhD Simina Raţiu

B2. Social dystopias Prof. Ştefan Borbély

B3. Postmodern dystopias MA Radu Conkan

MA Olga Ştefan

PhD Aura Ţeudan

C. Synthesis and taxonomy: Prof. Corin Braga

All domains and subdomains of research will be tackled simultaneously by the respective senior or young researchers. The collaboration between the researchers, the exchanges of information, bibliographies, books, etc., will ensure the coherence of the teamwork. The final synthesis will sum up the theoretical results and case analyses from each field and will combine the diachronic, historical approach with a paradigmatic, morphological approach.