Conferences

Romanian Studies Society 2025 International Conference

Voices and Silences

Cluj-Napoca, 29-31 May 2025

Colloque international De la parole au corps du monde. Lorand Gaspar à la croisée des langues, des cultures et des disciplines

Târgu-Mureș, les 27-28 février 2025

Utopian Studies Society / Europe 2023 Annual Conference

Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

July 5-7, 2023

Utopian Imaginaries

The Programme of the USS/E Conference is now online

For online participants: Each panel has a link to a zoom meeting

The timetable follows EEST (Eastern European Summer Time) (= +3 GMT)

The Conference is supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of Education, no. 152/E/DGIU/1/20.04.2023

Scientific Committee

Gregory Claeys (University of London, UK)

Sorin Antohi (Orbis Tertius Association, Bucharest, Romania)

Artur Blaim (University of Gdańsk, Poland)

Carmen Borbély (Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania)

Corin Braga (Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania)

Zsolt Czigányik (CEU Democracy Institute, Budapest, Hungary)

Executive Board

Corin Braga

Maria Barbu

Georgiana

Dan Chira

Paul Mihai Paraschiv

Constantin Tonu

Alex Văsieș

The French term l’imaginaire, as opposed to the traditional concepts of “imagination” and “fantasy”, is a seminal concept in the investigation of cultural, literary and artistic representations (see Braga, “Imagination, imaginaire, imaginal. Three French Concepts for Defining Creative Fantasy”, Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, vol. 6, no. 16, 2007, ISI indexed journal, http://jsri.ro/ojs/index.php/jsri/article/view/425). The modern concept of “the imaginary” was founded in the mid-20th century, through the works of Gaston Bachelard, Henry Corbin, Gilbert Durand (Les structures anthropologiques de l’imaginaire, Paris-Bruxelles-Montréal, Bordas, 1969) and other prominent philosophers. While “imagination” defines the human faculty of creating random mental images, with no correspondent in the outside reality, that is, false, chimerical representations, the French term imaginaire designates the imaging or the imagining function of the psyche, its capacity to create new representations. For Jean-Jacques Wunenburger, it designates the “inner creative force of imagination” (J.-J. Wunenburger, L’imaginaire, Paris, PUF, 2003).

Humans relate to the outside world not only through their senses and ideas, but also through images and representations. Their comprehension of the world and their ensuing reactions depend on these subjective images. As António Damásio and other neuroscientists have recently shown, the simple fact of telling stories (i.e. organizing our experience in narrative terms by means of brain maps) is one of the most elementary and archaic “obsessions of the brain”. Rather than something at the margins of the material and physical world (both visible and invisible), “the imaginary” is inextricably intertwined with it, over-determining the way we feel, read and represent (through artistic, literary, scientific, historical, religious or mythical discourses) both the reality enveloping us and the way we interact with and transform it. In order to understand human behaviour, anthropologists have to tackle the complex system of representations that underlies mental activity.

As an anthropological concept, “the imaginary” pervades all human practices. It applies to a vast range of domains, from sociology and religion to literature and the arts. Social imaginaries comprise narratives, mythical events, historical characters, and collective symbols that enable us to make sense of history, to organize the cultural memory and to configure the future. Charles Taylor defines “social imaginaries” as follows: “By social imaginary, I mean something much broader and deeper than the intellectual schemes people may entertain when they think about social reality in a disengaged mode. I am thinking, rather, of the ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations” (Modern Social Imaginaries, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2004, p. 23). Images of the self (autoimages) and of the other (heteroimages) (the “other” being conceived as an individual or as a collectivity), worldviews and outlooks on nature, the universe and God, representations of geography, history, society and culture, literary and fine arts fantasy, theatre and cinema, music and dance, advertising and media, etc. are all products and instruments of the imagining function. Even the most common and current attitudes of everyday life bear the imprint of collective habits and representations.

Researchers also talk about malfunctions and pathologies (“dérives pathologiques“) of the collective imagination (J.-J. Wunenburger, Imaginaires du politique, Paris, Ellipses, 2001). When they are no longer spontaneous and creative, collective images become stereotypes and clichés. Guided by ready-made representations, people no longer react individually to social stimuli, but engage in induced irrational attitudes, which lead to prejudices and conflicts and allow for manipulation and control. Social and cultural imaginaries are a common patrimony that could, on the one hand, consolidate and enhance clichés and behavioural inertia, and, on the other hand, reorient and transform recollections, expectations and hopes, projects and utopias. The imaginary is ambivalent: it can both prevent or put a stop to change and inspire or prompt new developments.

Since their creation, utopias have been designed as imaginary – in vitro – explorations of alternative worlds and societies. Utopian authors used them in order to make and unmake the current reality, to propose alternative models for the existing state of European civilization, and to investigate “les possibles latéraux” (F. Chirpaz, Raison et déraison de l’utopie, Paris, 1999) of the history. Utopias can be seen as successors of the medieval topic of the Terrestrial Paradise (cf. C. Braga, Du Paradis perdu à l’antiutopie aux XVIe-XVIIIe siècles, Paris, 2010). If, during the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, the Garden of Eden was presented as a lost paradise, closed by God after the original sin, during the Renaissance, humanistic optimism led various thinkers and writers, such as Morus, to the conclusion that the lost paradise could be replaced with a city of men. Utopias are human-made ideal places, where people governed by reasonable and moral principles achieve a perfect society. Nevertheless, utopian optimism was soon challenged by several theoretical critiques and institutional attacks, from the standpoint of Counter-Reformation theology, Cartesian rationalism, and English empiricism. These ideologies addressed a series of decisive counter-arguments to the hope that mankind could by itself establish a perfect society and a paradise on earth. Starting with Joseph Hall (Mundus alter et idem, 1605) and Artus Thomas (L’Isle des Hermaphrodites, 1605), an important number of authors took on official and public censorship and reshaped their fiction into critiques of utopian visions. Instead of imagining ideal places, they began to conceive counter-utopian societies and terrestrial infernos.

Historians of the European literature have distinguished between two main species of utopias: classical (16th-18th centuries) and modern (19th-20th centuries) (cf. M. Leslie, Renaissance Utopias and the Problem of History, Ithaca, 1998). Within this historical blueprint, it is possible to make the distinction between several corpuses and sub-genres of the utopian genre:

– Classical religious utopias and dystopias.

– Classical rationalist utopias and dystopias.

– Classical empirical utopias and dystopias.

– Modern scientist utopias and dystopias

– Modern social utopias and dystopias

– Postmodern utopias and dystopias

With postmodern relativism and “irrealism” (Searle, Goodman, Putnam, Maturana), not only the human capacity of constructing ideal societies and perfect cities, but the concept of reality itself has been questioned and deconstructed. Possible worlds are becoming as real as everyday reality in literature, films, and the arts. These parallel worlds are either superior to the one we are living in (which is a terrifying place, like in The Matrix, Dark City, etc.), or inferior, describing a nightmarish world we are heading to. Many dystopian (science-)fiction works imagine a future in which a disaster has already affected humanity. In the paper “A World Neither Brave Nor New: Reading Dystopian Fiction after 9/11” (Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, Volume 4, Number 1, January 2006), Efraim Sicher and Natalia Skaradol investigate the impact that September 11 had upon the conscience of the American public. In this tragic terrorist event, reality became a reiteration, an acting-out of a series of catastrophic movies made in Hollywood (the headquarters of the hyperreal, as Baudrillard put it). Literary and cinematic experiences have undergone a “pictorial turn”, to use Jacques Rancière’s term, as images are no longer qualified in terms of deficient or excessive consistency.

All this leads to a new partage du sensible, within the context of an altered status of image and text as extensively analysed and illustrated in studies and books of the last decade belonging to such writers as Jacques Rancière, Jean Luc Nancy, Derrida, Georges Didi-Huberman, Slavoj Žižek, Alain Badiou, etc. The micro-politics of the image interferes with the narrative in search of its own status between the real and the utopian. Utopian thinking becomes a powerful instrument in exploring, exposing and modelling the challenges of our contemporary society, the concerns, fears, hopes and projects targeting topics such as climate change, natural ecosystem decline, global resource depletion, our planet’s homeostasis, new social dynamics, migration and diaspora, fluid societies, race, gender, class, religious minorities and all forms of discrimination, the IT revolution, transhumanism, etc.

Topics might include:

– Utopian social or literary imaginaries

– Utopian modelling of natural and social systems

– Utopia vs. Dystopia: assessing secondary worlds

– Fictional worlds : utopias as “possibles latéraux” (Raymond Ruyer)

– Minoritarian (sexual, racial, natural) utopian / dystopian imaginaries

– Climate changes and ecocatastrophes

– Gaia hypothesis and Earth homeostasis

– Critical utopias / dystopias in contemporary pop culture

We invite panels and papers that, while dealing with an open-ended list of particular topics, engage (some of) the above-mentioned ideas, and focus on utopian fictions, projects, and experiences. Non-theme related interdisciplinary papers are also welcome.

Meeting with Andrei Codrescu, between two literatures

May 29, 2023, 13:00, room Popovici

Liudmyla Harmash, “Culture of resistance and culture of concord: Causes and possible consequences of the Russo-Ukrainian war”

Joi, 20 octombrie 2022, Facultatea de Litere, sala Popovici

Jean-Jacques Wunenburger

“Aprés la mort d’une reine, l’imaginaire de la monarchie”

Miercuri 26.10.2022, ora 12:00, Facultatea de Litere, sala Lucian Blaga

Presentation du volume La vie de l’esprit en Europe centrale et orientale depuis 1945. Dictionnaire encyclopedique, Sous la direction de Chantal Delsol et Joanna Nowicki, Les Editions du Cerf, Paris, 2021

Online bilingual conference: Diasporic Voices: Tears, Silences, Laughter

Babes-Bolyai University: The Center for Imagination Studies, The Centre for African Studies, The Center for Middle-Eastern and Mediterranean Studies

April14, 2022

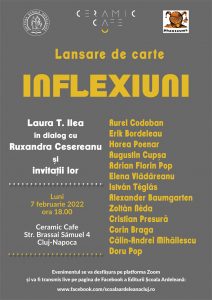

Presentation du volume Inflexiuni dirige par de Laura T. Ilea,

Institut Francais, Cluj-Napoca, 7 februarie 2022

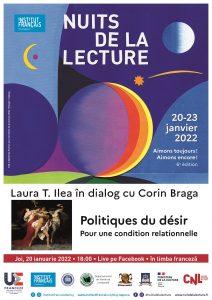

Politiques du désir. Dialogue entre lect. univ. dr. Laura T. Ilea și prof. univ. dr. Corin Braga,

Institut Francais – Cluj, joi, 20 ianuarie 2022, ora 18

https://institutfrancais.ro/cluj-napoca/nuits-de-la-lecture/

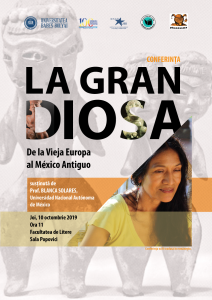

Conference Blanca Solares: La Gran Diosa. De la Vieja Europa al Mexico Antiguo

Facultatea de Litere, Cluj, 10 octombrie 2019

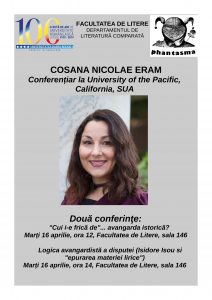

Conference Cosana Nicolae Eram : “Cui i-e frică de”… avangarda istorică?,

Logica avangardistă a disputei (Isidore Isou și “epurarea materiei lirice”)

Facultatea de Litere, Cluj, 16 aprilie 2019

Annual conference of ALGCR: Analogie, Comparație, Influență

Facultatea de Litere, Cluj, 14-15 iulie 2017

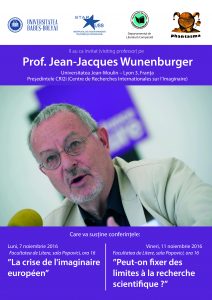

Conference Jean-Jacques Wunenburger: La crise de l’imaginaire européen,

Peut-on fixer des limites à la recherche scientifique ?,

Facultatea de Litere, Cluj, 7 și 11 noiembrie 2016

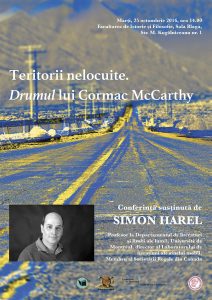

Conference Simon Harel: Teritorii nelocuite. Drumul lui Cormac McCarthy

Facultatea de Litere, Cluj, 25 octombrie 2016

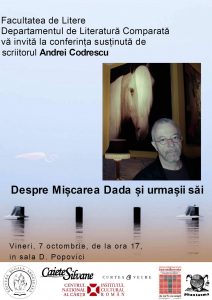

Conference Andrei Codrescu: Despre Mișcarea Dada și urmașii săi

Facultatea de Litere, Cluj, 7 octombrie 2016